I love old woodworking machines from the Golden Age of manufacturing. If it is cast iron and has some kind of floral pattern or gold leaf lettering my heart goes pitter-patter.

The Kregel Windmill Factory in Nebraska City, Nebraska

Dad taught me about steam power and line shafts and jackshafts in old shops and factories that we visited on family trips. I have even been in a few with the power on--the whole shop seemed to be alive when the belts were humming and idler pulleys were ticking over. As an industrial engineer I appreciate mechanical power and technical innovation. But as a traditional woodworker, I also have a nagging dread of the “dark side” of machines.

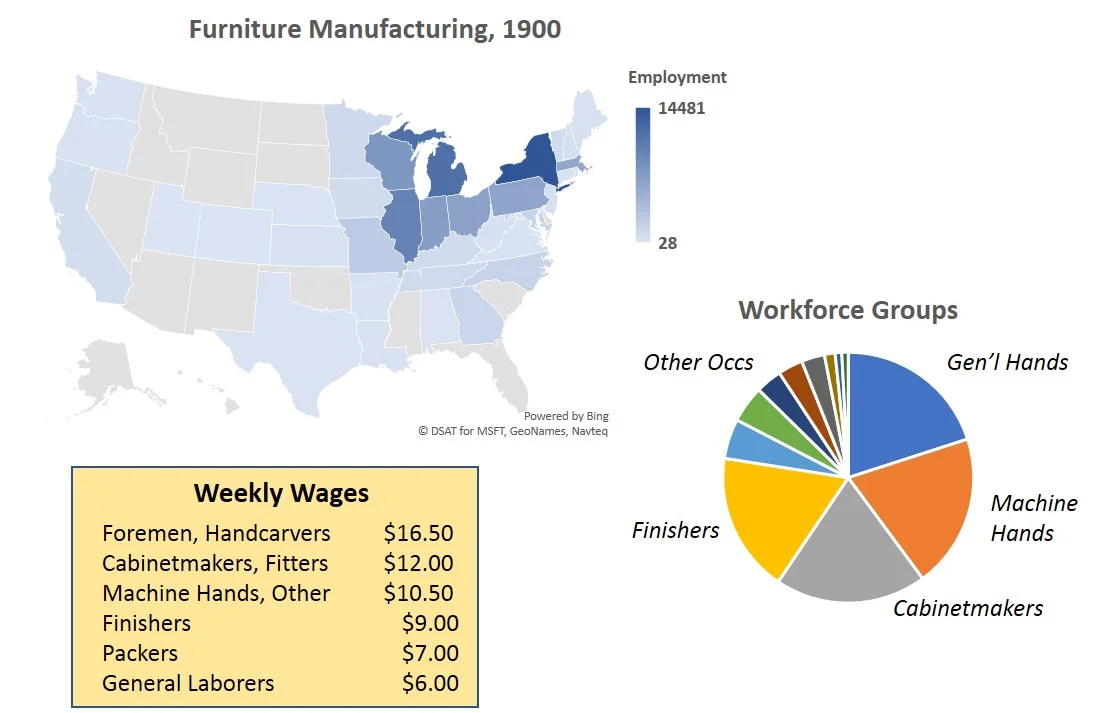

In 1900 there was a lot of angst about the mechanization of woodworking. Morris, Ruskin, and others in the Arts and Crafts movement decried the effects of mechanization on design and taste. Marx called out the dehumanizing effects of the rationalization of factory work (the alienation of labor). Health and safety conditions were deplorable. While I certainly wouldn’t want to be working in a turn-of-the-century furniture factory, mechanization drove the industry. Employment expanded dramatically, value of goods shipped rose, regional industrial development (forestry, logging, lumber mills, textile production) occurred in places like the Lake States and then in the Southern Piedmont. In the 12th US Census (1900), the survey of manufacturers showed skilled handcarvers still averaged $16.50 a week. Machine operators got about $10.50 a week.

Fast forward to 2017. American furniture manufacturing has experienced wrenching change. From 2000 to 2016, U.S. furniture manufacturing employment has gone from almost 700,000 to less than 400,000. Jobs lost primarily to overseas manufacturing where wages are only slightly higher ($0.50/hr) than they were in the U.S. in 1900. We didn't lose jobs to the machines, we lost jobs to low-wage competition in a global economy.